Promoting English Phonological Awareness in Japanese High School Students

Brett Reynolds

Brett Reynolds

Recent research into the psycholinguistics of reading strongly suggests that learning to read English with fluency and ease requires phonological awareness (Adams, 1990; Bryant & Goswami, 1987). Although it has been shown that even infants discriminate between language sounds and non language sounds, this is only tactic awareness (Henderson, 1986). The phonological awareness discussed here is the conscious, explicit awareness that allows people to identify, isolate, and otherwise manipulate language sounds. This ability is not only requisite for reading. Building strong, stable phonological representations of language likely facilitates all aspects of language learning from pronunciation to acquisition of vocabulary and grammar (Ellis, 1996).

Just as language can be broken down into progressively smaller units, phonological awareness seems to be a single construct that has different aspects. Researchers have proposed word, syllable, sub-syllable (onset and rime), and segmental (phonemic) levels. It also seems that awareness at the higher levels may precede awareness at lower levels.

Because of differences in writing systems (orthographies), Japanese children's phonological awareness is typically impoverished relative to that of their English L1 peers (for example). This is because Japanese writing is based on syllables or groups of syllables. This is called a syllabic orthography. English, Finnish, Arabic, and many other languages have writing systems that are based on phonemes. These are called alphabetic orthographies. Most researchers agree that one must learn to read an alphabetic orthography in order to gain phonemic awareness (Read et al., 1986).

In children, the teaching of L1 phonological awareness has been shown to be both possible and beneficial (Lundberg, Frost, and Peterson, 1988). In my own unpublished investigations, I have found that the phonological awareness of Japanese school children typically shows a regular progression from the beginning of junior high school through to the end of high school. Similarly, Allen found age of Japanese children to be a significantly related to phonological ability (1997). I have also found that with a minimum of instruction, Japanese junior high students can achieve scores on par with those of students four years their senior on a test of phonological awareness (unpublished data).

The benefits of phonological awareness have been shown to include long term gains in reading ability (Lundberg, Frost, and Peterson, 1988). Such reading gains often lead to bootstrapping effects and spread to improvements in vocabulary and general language ability (Stanovich, 1986). Although this research has been carried out with L1 readers, there seems to be no obvious reason why such training would not benefit Japanese EFL students equally, if not more than their English L1 peers.

What are they

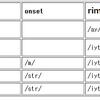

All syllables have a rime and many have onsets. The rime is the vowel sound in the syllable and anything that comes after it. The onset is whatever may come before the rime. Of course, words that end in the same rime are said to rhyme (e.g.. say, day; flower, hour).

Table 1. Onset and rime

Why are they important?

Being aware of rhyme is very helpful in learning to read and spell. Although English spelling is much criticized for the multitude of ways that each sound can be represented, the rimes in rhyming words tend to share spelling patterns. e.g.

bake, brake, cake, mistake

but: ache, opaque

gave, brave, misbehave

but: they've, waive

also consider: have

Onset spellings are even more reliable than rimes, often one hundred percent so. Proficient English readers commonly use analogies between the onset and rhyme of known words to guess the reading of unknown words. Even beginning readers can make use of such analogies (Goswami and Bryant, 1990). Japanese readers make similar analogies using the phonological elements in known kanji to guess the reading of unfamiliar characters (DeFrancis, 1989). While the reading of any given kanji is never smaller than a syllable, rimes are often sub-syllabic. Therefore, to apply this strategy of reading by analogy in English requires a deeper level of phonological awareness than it does in Japanese.

English speaking children become aware of rhyme often before they begin to read (Adams, 1990; Yopp, 1988). The use of rhyming is prevalent in English. In Japanese, however, although this concept exists, it is very rarely employed. In fact, the Japanese expression, in o fumu (to rhyme) is unknown to most young Japanese. Alliteration is also a common device in English but rarely employed in Japanese.

How can awareness be improved?

I have found that it takes very little instruction to get students to notice rhyming and alliteration. A basic explanation of the concept, along with a number of well chosen examples, gets them started. The following activities vary in their difficulty. They also tap different skills when they are done with print or orally.

up - lup, tup...

Seven super snakes say something slowly.

grape - ape

play, man - plan, may

If you have a computer, a good resource for finding rhyming words is The Semantic Rhyming Dictionary(available online).

What are they?

A phoneme is the smallest language sound whose insertion or removal or replacement makes a difference to meaning. The word, 'tape', has three phonemes; namely, /t/, /ey/, and /p/.

Why are they important?

Learning to read English beyond the initial stages requires one to grasp the alphabetic principle (Adams, 1990; Gough, Juel, and Griffith, 1992; Stanovich, 1986). The alphabetic principle is that individual sounds (phonemes) are represented by letters (graphemes). Obviously, without understanding that syllables can be broken into their component phonemes, one can not understand the alphabetic principle.

As mentioned above, Japanese is a syllabic language. There is no way to represent individual consonant phonemes in any of the three Japanese orthographies ( hiragana, katakana, and kanji ). Because of this, Japanese children do not gain phonemic awareness like their English speaking peers (Mann, 1986).

In designing the following activities, the teacher must be aware of Japanese phonology. Vowel insertion strategies (epenthesis) commonly used by Japanese EFL students can seriously reduce the value of these activities if words are not chosen to carefully with this in mind.

How can awareness be improved?

Phonemic awareness can be improved through both segmenting and blending activities. Segmenting activities include isolating or eliminating individual phonemes. e.g.

a - 1, the - 2, speak - 4

split - /s/ /p/ /l/ /I/ /t/, bright - /b/ /r/ /ay/ /t/

that - (th) (a) (t), foot - (f) (oo) (t)

speak - peak, speak - seek

Blending activities require the student to put phonemes together. e.g.

/s/ /p/ /l/ /I/ /t/ - split, /b/ /l/ /ow/ - blow

Some activities require both segmenting and blending skills :

meet - team, late - tail

this is in pig Latin - iss they izey iney igpey atinley

kite + apple + tie = cat

These exercises can mostly be done in a short amount of time (five minutes) with a minimum of preparation. Compared to the time investment needed, there is the potential for great returns. The presentation above is meant to reflect a general progression from easiest to hardest activities (Gough, Larson, and Yopp, online). There is no need to go through each in a step by step fashion. Instead, teachers are encouraged to find the activities they find the most useful and enjoyable. By examining the principles involved and the outcomes, teachers can easily adapt and expand the activities for their own classes.