Roles of Self-esteem in Second Language Oral Production Performance

Keiko Kazumata

Keiko Kazumata

Researchers have been studying a correlation between second language oral production tasks and various personality variables. Frequently explored traits include sociability, extroversion, field dependence/independence, empathy, and anxiety (Gardner & Clement, 1990). Brown (1994) lists self-esteem, inhibition, risk-taking, anxiety, empathy, and extroversion as personality factors. Furthermore, he considers second language learning strategies in relation with Myers-Briggs character types, which attempt to categorize personality according to combinations of four dichotomous styles of functioning: extroversion-introversion, sensing-intuition, thinking-feeling, judging-perceiving.

It is not easy to isolate a single personality trait that shows a statistically significant correlation with second language oral performance partly due to difficulties building a psychological inventory to test personality traits. Nonetheless, certain variables seem to have a major impact on learners' performance. One of the variables, a degree of self-esteem, cannot be eliminated in the discussion of personality factors of second language oral production tasks. In addition, in order to achieve high levels of speaking proficiency, one has to take risks with new knowledge in language as a normal course of learning. However, taking such risks has the potential to damage one's self-esteem. Therefore, risk-taking should be examined as a personality factor of oral performance in relation to self-esteem. Furthermore, flexible ego and a degree of task anxiety, locus of control, and attribution styles seem to have a strong link to self-esteem. Those variables are also powerful determinants of second language oral production performance.

Coopersmith, quoted in Brown (1994), defines self-esteem as the expression of "an attitude of approval or disapproval, and indicates the extent to which an individual believes himself to be capable, significant, successful, and worthy" (p. 137). In 1979, Adelaide Heyde studied the effects of self-esteem on performance of oral production tasks by American college students. The result showed positive correlation (Brown, 1994). Self-esteem, therefore, appears to be one of the indicators of successful French language learning. However, self-esteem is not an isolated variable. It is interwoven with several other personality variables.

Oral production tasks differ from reading and writing tasks by posing a greater potential for damage to damaging one's self-esteem in the process of second language acquisition. In a conversational setting, students do not have enough time to consult a dictionary for accurate pronunciation and grammar use before performance turns, whereas reading and writing tasks normally allow a student enough time to organize sentences and to find the most appropriate word. People with "healthy" self-esteem suffer no psychological damage when they are misunderstood and given negative feedback. On the other hand, a relatively insecure learner's fear of making a mistake and receiving unwanted feedback can impede experimentations with newly learned knowledge. As verbal rehearsal is necessary for information to be stored in the long-term memory (Weiten, 1989), this can impede language learning.

Another important factor in determining one's success in oral performance of second language is level of inhibition. Inhibition refers to the degree to which individuals allow their ego boundary to be open to a new set of knowledge and value systems. Brown (1994) describes the "language ego", a concept coined by Guiora. He says:

The human ego encompasses what Guiora called the language ego to refer to the very personal, egoistic nature of second language acquisition. Meaningful language acquisition involves some degree of identity conflict as language learners take on anew identity with their newly acquired competence (p. 138).

The issue of language ego is relevant in light of the acculturation that often accompanies language learning. Language is expressions of one's thought and value systems which are reflections of culture where the language is being spoken. When learning another language, the established ego is at stake and one's self-esteem becomes fragile. Kleinjans writes:

"All cultures provide men with facades to protect their egos. However, that which serves as a facade in his own culture may be striped away by exposure to another culture and the learner may suddenly find himself standing psychologically naked. Therefore, the main prerequisites to second culture learning are receptivity, plus normal intelligence, and a good measure of inner security " (Cited in Damen & Savignon, 1987, p. 216).

Self-esteem, however, is not the single determinant of receptivity to a second culture. Motivation is an equally powerful force that drives an individual to learn and acquire a second cultural system and new identity. I have personally witnessed that students in U. S. colleges, who acted more Americanized, were those who were trying to obtain permanent residency in the U. S.. Their pronunciation was not always native-like. However, students, who retained their Japanese ways (dated Japanese, planned or wanted to come back to Japan after graduation), seemed consistently to have stronger Japanese accents.

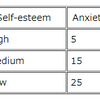

A personality variable closely related to self-esteem is anxiety. Overall, anxiety is negatively correlated with self-esteem. Anxiety is feelings associated with uneasiness, frustration, self-doubt, apprehension, and worry (Brown, 1994). According to Coopersmith's 1975 study, an inverse relation between anxiety and self-esteem was found (See Table 1).

Table 1: Anxiety scores for boys with different levels of self-esteem

Note. The amount of anxiety experienced by three groups of boys was measured by the frequency of their reported feelings of distress and the frequency of psychosomatic symptoms as reported by their mothers. Source: Weiten, 1989, p. 465

Anxiety is further divided into two levels: global or trait anxiety and situational or state anxiety (Brown, 1994). State anxiety comes in many forms, such as test anxiety. Foreign language anxiety is one form of state anxiety. A number of studies were conducted from 1968 through 1980 by Clement, Gardner, Smythe, Tarampi, Lambert, and Tucker on the relationship between various types of anxiety and second language performance (Gardner & Clement, 1990). Results of these studies show that anxiety measures that are not directly related to second language anxiety fail to show any correlation with achievement (Gardner & Clement, 1990). However, Chastain in a 1975 study, found an inverse relationship between test anxiety and grades in Spanish. Nonetheless, the same correlation was not found for German, or French (Gardner & Clement, 1990). In later studies, Young in 1991, Phillips in 1992, and others concluded that "foreign language anxiety can be distinguished from other types of anxiety and that it can have a negative effect on the language learning process" (MacIntyre & Gardner, cited by Brown, 1994).

Low self-esteem is related to a desire for competency, mastery, achievement, strength, adequacy, confidence, and independence (Liebert & Spiegler, 1990). In other words, people with low self-esteem have higher tendencies to believe that events that happen in life are beyond their control, whereas people with high self-esteem believe in their ability to influence events and others. Such beliefs can apply to the concept of locus of control, originally described by Rotter in the 1950s (Williams & Burden, 1997). Individuals with an internal locus of control tend to believe that they are responsible for their successes and failures. Conversely, people with the external locus of control tend to attribute successes and failures to luck, chance, or fate (Williams & Burden, 1997).

The locus of control scale consists of forty yes-no questions. Its test-retest reliability and validity have been proven respectable (unknown author, used as a lecture material at Michigan State University 1989). It would be a good idea to administer the test in the beginning of a course in order to discover students' locus of control. It would also be useful to use the scale when a teacher encounters slow progress in a particular student. Locus of control scale and its scoring information are provided in the appendix.

Some internal shifts of students' locus of control are possible through proper teacher encouragement. Teachers can foster responsibilities and confidence in students by empowerment. Empowering students with a sense of confidence will also raise their self-esteem. Therefore, changes in the overall learning attitude could occur. How could it be done? Williams and Burden (1997) list some ways to accomplish this objective. Encourage students to:

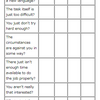

Closely related to the concept of locus of control is Heider's attribution theory developed in the 1940s and 50s. The central aspect of his theory states that it is how people perceive events rather than the events in themselves that influence behavior (Williams & Burden, 1997). Since the locus of control scale is quite lengthy and some questions are not related to language learning and thus its validity in the application to language skills could be questionable, the attribution assessment developed by Williams and Burden can be used as an alternative (see Table 2).

Table 2: Attribution profile questionnaire

Source: Williams & Burden, 1997, p. 108

Empowering students can raise levels of self-esteem and consequently improve pronunciation. A direct method of empowerment is to equip students with self-correcting and self-monitoring abilities. Self-correction is the "ability to correct oneself when a pronunciation error has been pointed out" (Firth, 1997, p.215). At this point, a student still relies on teacher instruction. A further step, self-monitoring, or the "ability to listen for and recognize errors" (Firth, 1997, p.215) is necessary for students to realize their ability to teach themselves. Firth (1997) writes that mastery of self-correction involves concise teaching and appropriate feedback. The teaching includes discussion of reference books as an aid to self-correction. In teaching pronunciation, the teacher should involve as many senses as possible. Furthermore, she writes that a simple mnemonic "peg" should be taught to students so that they can use the peg to remember the correct pronunciation. When a student pronounce a word incorrectly, instead of giving the student the right pronunciation, the teacher feedback should be given only to remind the student that a nonstandard version has been used. Firth lists three ways to elicit this "reminding":

"1. Repeat the incorrect sound using stress and intonation to suggest a questioning attitude.

2. Query the word containing the incorrect sound by replacing it with the question word "what."

Repeat the student's error, exaggerating the incorrect pronunciation" (p. 217).

Finally, once students learn how to self-correct errors, they have to learn ways to do self-monitoring. The ability to realize one's own error and fix it is essential for real learning to take place. After a certain point, a teacher's role should shift to that of a resource provider from that of a direct instructor. True mastery depends on the ability of self-teaching. Below is a direct excerpt taken from Firth (1997) about the techniques for developing self-monitoring:

"1. Have students determine the accuracy of their own pronunciation by using a 'peg'. For example, in producing a /w/, the student should ask 'Have I used both lips? Does it sound like a /v/ or a /w/?'

After choral and individual practice a form, have students tape their own speech, reading from a written text. Prior to taping have them mark the text for breath groups, stressed and unstressed words, intonation patterns, linking, etc., much in the same way as an actor would in preparing a script. During the listening phase, have students replay the tape several times, focusing on one aspect of pronunciation only during each replay. The teacher can then check the students' monitoring by listening to the tape and commenting on the accuracy of the evaluation.

During more communicative activities, have students select one area of pronunciation to focus on (e.g. speed of delivery). Have them judge their own performance and also have a partner or class member judge their pronunciation accuracy. Compare the two opinions.

In order to self-monitor outside the class, students must know which areas of pronunciation to focus on. They should establish priorities and work on one problem at a time, paying particular attention to this whenever they speak. Peers in the workplace can be asked to help them monitor specific problems" (p. 218-219).

Actualization of self-monitoring mastery could be a long process. However, true joy of learning is found where an individual finds his own power to learn. Language teachers have the potential to enhance students' confidence and help them to find a new purpose in life with the newly acquired skills.

The degree of self-esteem is hypothesized to be correlated with success in second language acquisition, especially in tasks involving oral performance. Studies show the positive correlation between self-esteem and oral performance. Other factors such as risk-taking, inhibition, anxiety, locus of control, and attribution style also seem to be related significantly to the degree of self-esteem. These variables are also factors determining students' success in oral production tasks.

In the classroom, teachers should incorporate techniques to enhance students' self-esteem as a part of their pedagogical philosophy. This can be facilitated by instructing students in self-correcting and self-monitoring skills. Giving students the power to self-teach, will allow them to gain confidence over learning. An increase in language-related task self-esteem is anticipated to follow.

Locus of Control Scale

Instructions

Answer the following questions the way you feel. There are no right or wrong answers. Don't take too much time answering any one question, but try to answer them all. It is not unusual to wonder, "What should I do if I can answer both yes and no to a question?" If you do, think about whether your answer is just a little more one way than the other. For example, if you'd assign a weighting of 51 percent to "yes" and assign 49 percent to "no," mark the answer, "yes." Try to pick one or the other response for all questions and not leave any blank. Mark your response to the question in the space provided on the left.

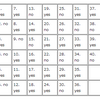

Scoring the Scale

Circle your yes or no response each time it corresponds to the keyed response below. Add up the number of responses you circle, and this total is your score on the Locus of Control Scale. Record your score below.

Table 3: Locus of control scale scoring key

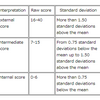

Interpreting the Score

Table 4: Norms

Source: lecture materials used in Personality Psychology, Michigan State University, 1989.